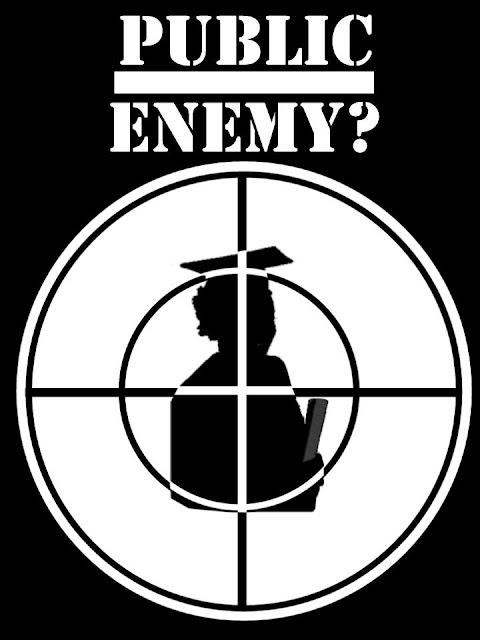

Fear of a Black-Planned Ed?

This is a longer version of an article published in Vue Weekly in the week of 2008 February 28 for a series of articles commissioned for African History Month.

One of the most obvious indicators of injustice is the use of double-standards. We learn early in life that what’s good for the goose is good for the gander. If geese are eating gravel and ganders and getting grain—and worse, the gander lobby is raising hell about geese wanting to get some—you know that someone is having the down pulled over his eyes. And that’s usually a prelude to getting roasted.

The last several months in Toronto have been a furious battle over the just-approved proposal to create an Africentric public school as one means to address the disproportionate failure and drop-out rate of African-Canadian students in that district.

But to hear Paula Todd on CTV Newsnet’s The Verdict—just one of a wailing chorus of opposition—such a school would be a return to American-style racial segregation and a betrayal of the very students it’s supposed to be helping. Todd’s producers even helpfully ran the word “segregation” as a subtitle on the screen throughout a lengthy debate they hosted, a word that immediately shaped the impressions of viewers who might be channel-surfing or even channel-squatting.

Segregation? Huh?

It might be segregation, if, for instance, when you leave work or school to return to your own home instead of someone else’s, you’d call that segregation. Or, for that matter, when you go to your own workplace instead of someone’s, that were segregation.

Why is there such terror among some elements of our society about Africentric education? What assumptions are behind the terror? When scores of other groups have their educational needs met in publicly-funded schools—officials call it “school choice,” but African-Canadians are denied such choice, it’s clearly a double-standard. If Todd and her types are so concerned that “segregated” education will “roll back the clock” and ill-prepare students for “integrated” communities and workplaces, why are they silent aboutEdmonton ?

In Edmonton alone, we have two First Nations schools (Amiskwaciy Academy, Awasis), a Hebrew bilingual school (Talmud Torah), three Arabic bilingual schools (Glengarry, Malmo and Killarney), three Spanish bilingual (Mill Creek, Sweet Grass, McKernan), four Christian schools, four Ukrainian bilingual schools, five German bilingual schools, twelve schools with Mandarin bilingual programme, and seventeen schools offering French immersion.

We also have a girls school (Nellie McClung), a “child study centre” (Garneau), a dance school (Vimy Ridge), a science school (Elmwood), a “traditional” school (James Gibbons), two hockey schools (Donnan and Vimy Ridge), four arts schools, four “sports alternative” schools, four “academic” schools, eight “pre-advanced placement” junior highs, and eight schools offering a foreign curriculum (International Baccalaureate).

And I haven’t even mentioned a single Catholic school. Forget about Catholic specialty schools. Their entire national, tax-funded system is all “special interest,” and by Todd’s standard “segregated.” But then again, with the exception of Aboriginal Canadians (who are the “subject” of an entire federal department), few of these groups are the target of racial profiling by police, courts or employers.

Some claim that failure among African-Canadian and African-American students is a defect in “Black” culture, that the kids equate academic success with racial betrayal or “acting White.”

That notion was popularised by Nigerian-American academic John Ogbu in Black American Students in an Affluent Suburb, among others, and thoroughly debunked by African-American sociologist Algernon Austin in Getting It Wrong: How Black Public Intellectuals are Failing BlackAmerica

The original “acting White” claims were never made by or even put to students; the phrase was a post-study quip used by the researchers and picked up by media.Austin ’s study reveals that, in the US Austin Tuskegee and Morehouse.

Jenny Kelly, author of Under the Gaze: Learning to Be Black in a White Society and an Education professor at the U of A, notes that some various communities in majority-White countries have advocated Africentric schools as means for student success, including in her nativeEngland

InCanada Toronto , where the community is large, calls have been made for years, and in Edmonton

Kelly herself is not an advocate of such schools, having argued extensively that moving towards such institutions lowers pressure on school boards and governments to improve all public schools, including through the pan-disciplinary infusion of global African content into the curriculum. Nor is she executing a double standard, since “all kids should be educated in one school [system, even] in terms of religious groups including Catholics or whomever else. There’s a publicly funded space and kids should be educated in that space.”

“We live in a society that is not a level playing field. Issues of race, class and gender exist within that space. When we look at the research, at anecdotes, race is an issue in kids’ lives—in terms of low expectations [from authorities], and in terms of dropping out.” Kelly points to the significant research on drop-out and “push-outs” by George Dei, Chair of the U of T’s Sociology and Equity Studies department at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education. “It’s often the conditions within the school that somehow enable and encourage kids to drop out. So what do you do? These kids are dropping out, they don’t seem to be able to survive in the traditional system. The system isn’t changing fast enough to take them up—what do you do?”

And that, she says, is a major part of the rationale for Africentric schools. “It’s an alternative within a larger system. If it provides a space that some students would find effective in which to learn, then I say, go with it.” She’s clear she wouldn’t want such schools to have mandatory attendance or exclusion by race, but she acknowledges that no one is advocating such requirements.

When and if such schools go forward, Kelly’s main concern is operational: “Who is going to fund this? What’s the role of the province? Will Black parents have to fund-raise? If they’re going to be operating in the long term, and not just the short term, funding is important. The kids need to get a really good education, not just a second-hand ‘We meet every so often.’” She’s clear on the absolute must-haves: “Good teachers, good resources and a good curriculum.”

The last several months in Toronto have been a furious battle over the just-approved proposal to create an Africentric public school as one means to address the disproportionate failure and drop-out rate of African-Canadian students in that district.

But to hear Paula Todd on CTV Newsnet’s The Verdict—just one of a wailing chorus of opposition—such a school would be a return to American-style racial segregation and a betrayal of the very students it’s supposed to be helping. Todd’s producers even helpfully ran the word “segregation” as a subtitle on the screen throughout a lengthy debate they hosted, a word that immediately shaped the impressions of viewers who might be channel-surfing or even channel-squatting.

Segregation? Huh?

It might be segregation, if, for instance, when you leave work or school to return to your own home instead of someone else’s, you’d call that segregation. Or, for that matter, when you go to your own workplace instead of someone’s, that were segregation.

Why is there such terror among some elements of our society about Africentric education? What assumptions are behind the terror? When scores of other groups have their educational needs met in publicly-funded schools—officials call it “school choice,” but African-Canadians are denied such choice, it’s clearly a double-standard. If Todd and her types are so concerned that “segregated” education will “roll back the clock” and ill-prepare students for “integrated” communities and workplaces, why are they silent about

In Edmonton alone, we have two First Nations schools (Amiskwaciy Academy, Awasis), a Hebrew bilingual school (Talmud Torah), three Arabic bilingual schools (Glengarry, Malmo and Killarney), three Spanish bilingual (Mill Creek, Sweet Grass, McKernan), four Christian schools, four Ukrainian bilingual schools, five German bilingual schools, twelve schools with Mandarin bilingual programme, and seventeen schools offering French immersion.

We also have a girls school (Nellie McClung), a “child study centre” (Garneau), a dance school (Vimy Ridge), a science school (Elmwood), a “traditional” school (James Gibbons), two hockey schools (Donnan and Vimy Ridge), four arts schools, four “sports alternative” schools, four “academic” schools, eight “pre-advanced placement” junior highs, and eight schools offering a foreign curriculum (International Baccalaureate).

And I haven’t even mentioned a single Catholic school. Forget about Catholic specialty schools. Their entire national, tax-funded system is all “special interest,” and by Todd’s standard “segregated.” But then again, with the exception of Aboriginal Canadians (who are the “subject” of an entire federal department), few of these groups are the target of racial profiling by police, courts or employers.

Some claim that failure among African-Canadian and African-American students is a defect in “Black” culture, that the kids equate academic success with racial betrayal or “acting White.”

That notion was popularised by Nigerian-American academic John Ogbu in Black American Students in an Affluent Suburb, among others, and thoroughly debunked by African-American sociologist Algernon Austin in Getting It Wrong: How Black Public Intellectuals are Failing Black

The original “acting White” claims were never made by or even put to students; the phrase was a post-study quip used by the researchers and picked up by media.

Jenny Kelly, author of Under the Gaze: Learning to Be Black in a White Society and an Education professor at the U of A, notes that some various communities in majority-White countries have advocated Africentric schools as means for student success, including in her native

In

Kelly herself is not an advocate of such schools, having argued extensively that moving towards such institutions lowers pressure on school boards and governments to improve all public schools, including through the pan-disciplinary infusion of global African content into the curriculum. Nor is she executing a double standard, since “all kids should be educated in one school [system, even] in terms of religious groups including Catholics or whomever else. There’s a publicly funded space and kids should be educated in that space.”

“We live in a society that is not a level playing field. Issues of race, class and gender exist within that space. When we look at the research, at anecdotes, race is an issue in kids’ lives—in terms of low expectations [from authorities], and in terms of dropping out.” Kelly points to the significant research on drop-out and “push-outs” by George Dei, Chair of the U of T’s Sociology and Equity Studies department at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education. “It’s often the conditions within the school that somehow enable and encourage kids to drop out. So what do you do? These kids are dropping out, they don’t seem to be able to survive in the traditional system. The system isn’t changing fast enough to take them up—what do you do?”

And that, she says, is a major part of the rationale for Africentric schools. “It’s an alternative within a larger system. If it provides a space that some students would find effective in which to learn, then I say, go with it.” She’s clear she wouldn’t want such schools to have mandatory attendance or exclusion by race, but she acknowledges that no one is advocating such requirements.

When and if such schools go forward, Kelly’s main concern is operational: “Who is going to fund this? What’s the role of the province? Will Black parents have to fund-raise? If they’re going to be operating in the long term, and not just the short term, funding is important. The kids need to get a really good education, not just a second-hand ‘We meet every so often.’” She’s clear on the absolute must-haves: “Good teachers, good resources and a good curriculum.”

Comments